Catching keyboard interruptions in a Python script for a more orderly exit

17th April 2024A while back, I was using a Python script to watch a folder and process photos in there, whenever a new one was added. Eventually, I ended up with a few of these because I was unable to work out a way to get multiple folders watched in the same script.

In each of them, though, I needed a tidy way to exit a running script in place of the stream of consciousness that often emerges when you do such things to it. Because I knew what was happening anyway, I needed a script to terminate quietly and set to uncover a way to achieve this.

What came up was something like the code that you see below. While I naturally did some customisations, I kept the essential construct to capture keyboard interruption shortcuts, like the use of CTRL + C in a Linux command line interface.

if __name__ == '__main__':

try:

main()

except KeyboardInterrupt:

print('Interrupted')

try:

sys.exit(130)

except SystemExit:

os._exit(130)What is happening above is that the interruption operation is captured in a nested TRY/EXCEPT block. The outer block catches the interruption, while the inner one runs through different ways of performing the script termination. For the first termination function call, you need to call the SYS package and the second needs the OS one, so you need to declare these at the start of your script.

Of the two, SYS.EXIT is preferable because it invokes clean-up activities while OS._EXIT does not, which might explain the “_” prefix in the second of these. In fact, calling SYS.EXIT is not that different to issuing RAISE SYSTEMEXIT instead because that lies underneath it. Here OS._EXIT is the fallback for when SYS.EXIT fails, and it is not all that desirable given the abrupt action that it invokes.

The exit code of 130 is fed to both, since that is what is issued when you terminate a running instance of an application on Linux anyway. Using 0 could negate any means of picking up what has happened if you have downstream processing. In my use case, everything was standalone, so that did not matter so much.

Avoiding permissions, times or ownership failure messages when using rsync

22nd April 2023The rsync command is one that I use heavily for doing backups and web publishing. The latter means that it is part of how I update websites built using Hugo because new and/or updated files need uploading. The command also sees usage when uploading files onto other websites as well. During one of these operations, and I am unsure now as to which type is relevant, I encountered errors about being unable to set permissions.

The cause was the encompassing -a option. This is a shorthand for -rltpgoD, and the individual options perform the following:

-r: recursive transfer, copying all contents within a directory hierarchy

-l: symbolic links copied as symbolic links

-t: preserve times

-p: preserve permissions

-g: preserve groups

-o: preserve owners

-D: preserve device and special files

The solution is to some of the options if they are inappropriate. The minimum is to omit the option for permissions preservation, but others may not apply between different servers either, especially when operating systems differ. Removing the options for preserving permissions, groups and owners results in something like this:

rsync -rltD [rest of command]

While it can be good to have a more powerful command with the setting of a single option, it can mean trying to do too much. Another way to avoid permissions and similar errors is to have consistency between source and destination files systems, but that is not always possible.

Why all the commas?

4th December 2022In recent times, I have been making use of Grammarly for proofreading what I write for online consumption. That has applied as much to what I write in Markdown form as it has for what is authored using content management systems like WordPress and Textpattern.

The free version does nag you to upgrade to a paid subscription, but is not my main irritation. That would be its inflexibility because you cannot turn off rules that you think intrusive, at least in the free version. This comment is particularly applicable to the unofficial plugin that you can install in Visual Studio Code. To me, the add-on for Firefox feels less scrupulous.

There are other options though, and one that I have encountered is LanguageTool. This also offers a Firefox add-on, but there are others not only for other browsers but also Microsoft Word. Recent versions of LibreOffice Writer can connect to a LanguageTool server using in-built functionality, too. There are also dedicated editors for iOS, macOS or Windows.

The one operating that does not get specific add-on support is Linux, but there is another option there. That uses an embedded HTTP server that I installed using Homebrew and set to start automatically using cron. This really helps when using the LanguageTool Linter extension in Visual Studio Code because it can connect to that instead of the public API, which bans your IP address if you overuse it. The extension is also configurable with the ability to add exceptions (both grammatical and spelling), though I appear to have enabled smart formatting only to have it mess up quotes in a Markdown file that then caused Hugo rendering to fail.

Like Grammarly, there is an online editor that offers more if you choose an annual subscription. That is cheaper than the one from Grammarly, so that caused me to go for that instead to get rephrasing suggestions both in the online editor and through a browser add-on. It is better not to get nagged all the time…

The title may surprise you, but I have been using co-ordinating conjunctions without commas for as long as I can remember. Both Grammarly and LanguageTool pick up on these, so I had to do some investigation to find a gap in my education, especially since LanguageTool is so good at finding them. What I also found is how repetitive my writing style can be, which also means that rephrasing has been needed. That, after all, is the point of a proofreading tool, and it can rankle if you have fixed opinions about grammar or enjoy creative writing.

Putting some off-copyright texts from other authors triggers all kinds of messages, but you just have to ignore these. Turning off checks needs care, even if turning them on again is easy to do. There, however, is the danger that artificial intelligence tools could make writing too uniform, since there is only so much that these technologies can do. They should make you look at your text more intently, though, which is never a bad thing because computers still struggle with meaning.

Moves to Hugo

30th November 2022What amazes me is how things can become more complicated over time. As long as you knew HTML, CSS and JavaScript, building a website was not as onerous as long as web browsers played ball with it. Since then, things have got easier to use but more complex at the same time. One example is WordPress: in the early days, themes were much simpler than they are now. The web also has got more insecure over time, and that adds to complexity as well. It sometimes feels as if there is a choice to make between ease of use and simplicity.

It is against that background that I reassessed the technology that I was using on my public transport and Irish history websites. The former used WordPress, while the latter used Drupal. The irony was that the simpler website was using the more complex platform, so the act of going simpler probably was not before time. Alternatives to WordPress were being surveyed for the first of the pair, but none had quite the flexibility, pervasiveness and ease of use that WordPress offers.

There is another approach that has been gaining notice recently. One part of this is the use of Markdown for web publishing. This is a simple and distraction-free plain text format that can be transformed into something more readable. It sees usage in blogs hosted on GitHub, but also facilitates the generation of static websites. The clutter is absent for those who have no need of the Gutenberg Editor on WordPress.

With the content written in Markdown, it can be fed to a static website generator like Hugo. Using defined templates and fixed assets like CSS together with images and other static files, it can slot the content into HTML files very speedily since it is written in the Go programming language. Once you get acclimatised, there are no folder structures that cannot be used, so you get full flexibility in how you build out your website. Sitemaps and RSS feeds can be built at the same time, both using the same input as the HTML files.

In a nutshell, it automates what once needed manual effort used a code editor or a visual web page editor. The use of HTML snippets and layouts means that there is no necessity for hand-coding content, like there was at the start of the web. It also helps that Bootstrap can be built in using Node, so that gives a basis for any styling. Then, SCSS can take care of things, giving even more automation.

Given that there is no database involved in any of this, the required information has to be stored somewhere, and neither the Markdown content nor the layout files contain all that is needed. The main site configuration is defined in a single TOML file, and you can have a single one of these for every publishing destination; I have development and production servers, which makes this a very handy feature. Otherwise, every Markdown file needs a YAML header where titles, template references, publishing status and other similar information gets defined. The layouts then are linked to their components, and control logic and other advanced functionality can be added too.

Because static files are being created, it does mean that site searching and commenting, or contact pages cannot work like they would on a dynamic web platform. Often, external services are plugged in using JavaScript. One that I use for contact forms is Getform.io. Then, Zapier has had its uses in using the RSS feed to tweet site updates on Twitter when new content gets added. Though I made different choices, Disqus can be used for comments and Algolia for site searching. Generally, though, you can find yourself needing to pay, particularly if you need to remove advertising or gain advanced features.

Some comments service providers offer open source self-hosted options, but I found these difficult to set up and ended up not offering commenting at all. That was after I tried out Cactus Comments only to find that it was not discriminating between pages, so it showed the same comments everywhere. There are numerous alternatives like Remark42, Hyvor Talk, Commento, FastComments, Utterances, Isso, Mouthful, Muut and HyperComments but trying them all out was too time-consuming for what commenting was worth to me. It also explains why some static websites even send readers to Twitter if they have something to say, though I have not followed this way of working.

For searching, I added a JavaScript/JSON self-hosted component to the transport website, and it works well. However, it adds to the size of what a browser needs to download. That is not a major issue for desktop browsers, but the situation with mobile browsers is such that it has a sizeable effect. Testing with PageSpeed and Lighthouse highlighted this, even if I left things as they are. The solution works well in any case.

One thing that I have yet to work out is how to edit or add content while away from home. Editing files using an SSH connection is as much a possibility as setting up a Hugo publishing setup on a laptop. After that, there is the question of using a tablet or phone, since content management systems make everything web based. These are points that I have yet to explore.

As is natural with a code-based solution, there is a learning curve with Hugo. Reading a book provided some orientation, and looking on the web resolved many conundrums. There is good documentation on the project website, while forum discussions turn up on many a web search. Following any research, there was next to nothing that could not be done in some way.

Migration of content takes some forethought and took quite a bit of time, though there was an opportunity to carry some housekeeping as well. The history website was small, so copying and pasting sufficed. For the transport website, I used Python to convert what was on the database into Markdown files before refining the result. That provided some automation, but left a lot of work to be done afterwards.

The results were satisfactory, and I like the associated simplicity and efficiency. That Hugo works so fast means that it can handle large websites, so it is scalable. The new Markdown method for content production is not problematical so far apart from the need to make it more portable, and it helps that I found a setup that works for me. This also avoids any potential dealbreakers that continued development of publishing platforms like WordPress or Drupal could bring. For the former, I hope to remain with the Classic Editor indefinitely, but now have another option in case things go too far.

Solving error code 8000101D in SAS

26th November 2022Recently, I encountered the following kind of message when reading an Excel file into SAS using PROC IMPORT:

ERROR: Error opening XLSX file -> xxx-.xlsx . It is either not an Excel spreadsheet or it is damaged. Error code=8000101D

Requested Input File Is Invalid

ERROR: Import unsuccessful. See SAS Log for details.

Naturally, thoughts arise regarding the state of the Excel file when you see a message like this but that was not the case because the file opened successfully in Excel and looked OK to me. After searching on the web, I found that it was a file permissions issue. The actual environment that I was using at the time was entimICE and I had forgotten to set up a link that granted read access to the file. Once that was added, the problem got resolved. In other systems, checking on file system permissions is needed even if the message seems to suggest that you are experiencing a file integrity problem.

More user interface font scaling options in Adobe Lightroom Classic

25th November 2022Earlier in the year, I upgraded my monitor to a 34-inch widescreen Iiyama XUB3493WQSU. At the time, I was in wonderment at what I was doing even if I have grown used to it now. For one thing, it made the onscreen text too small so I ended up having to scale things up in both Linux and Windows. The former proved to be more malleable than the latter and that impression also applies to the main subject of this piece.

What I also found is that I needed to scale the user interface font sizes within Adobe Lightroom Classic running within a Windows virtual machine on VirtualBox. That can be done by going to Edit > Preferences through the menus and then going to the Interface tab in the dialogue box that appears where you can change the Font Size setting using the dropdown menu and confirm changes using the OK button.

However, the range of options is limited. Medium appears to be the default setting while the others include Small, Large, Larger and Largest. Large scales by 150%, Larger by 200% and Largest by 250%. Of these, Large was the setting that I chose though it always felt too big to me.

Out of curiosity, I decided to probe further only to find extra possibilities that could be selected by direct editing of a configuration file. This file can be found in C:\Users\[user account]\AppData\Roaming\Adobe\Lightroom\Preferences and is called Lightroom Classic CC 7 Preferences.agprefs. In there, you need to find the line containing AgPanel_baseFontSize and change the value enclosed within quotes and save the file. Taking a backup beforehand is wise even if the modification is not a major one.

The available choices are scale125, scale140, scale150, scale175, scale180, scale200 and scale250. Some of these may be recognisable as those available through the Lightroom Classic user interface. In my case, I chose the first on the list so the line in the configuration file became:

AgPanel_baseFontSize="scale125"

There may be good reasons for the additional options not being available through the user interface but things are working out OK for me for now. It is another tweak that helps me to get used to the larger screen size and its higher resolution.

Getting a Windows 11 Guest to run smoothly on VirtualBox

23rd November 2022In recent days, I have been trying to get Windows 11 to run smoothly within a VirtualBox virtual machine, and there has been a lot of experimentation along the way. This was to eradicate intermittent freezes that escalated CPU usage and necessitated hard restarts. If I was to use Windows 11 as a long-term replacement for Windows 10, these needed to go.

An internet search showed that others faced the same predicament but a range of proposed solutions did nothing for me. The suggestion of enabling 3D graphics capability did nothing but produce a black screen at startup time so that was not a runner. It might have been the combination of underlying graphics hardware and the drivers on my Linux Mint machine that hindered me when it helped others.

In the end, a look at the bug tracker for Windows guest operating systems running on VirtualBox sent me in another direction. The Paravirtualisation interface also may have caused issues with Windows 10 virtual machines since these were all set to KVM. Doing the same for Windows 11 seems to have stopped the freezing behaviour so far. It meant going to the virtual machine settings, navigating to System > Acceleration and changing the dropdown menu value from Default to KVM before clicking on the OK button.

Before that, I have been blaming the newness of VirtualBox 7 (it is best not to expect too much of a fresh release bringing such major changes) and even the way that I installed Windows 11 using the streamlined installation or licensing issues. Now that things are going better, it may have been a lesson from Windows 10 that I had forgotten. The EFI, Secure Boot and TPM 2.0 requirements of Windows 11 also blindsided me, especially given the long wait for VirtualBox to add such compatibility, but that is behind me at this stage.

Windows 11 is not perfect but Start11 makes it usable and the October 2025 expiry for Windows 10 also focuses my mind. It is time to move over for sake of future-proofing if nothing else. In time, we may get a better operating system as Windows 11 matures and some minds surely are thinking of a “Windows 12”. However things go, it may be that we get to a point where something vintage in the nature of Windows XP, Windows 7 or Windows 10 appears. Those older versions of Windows became like old gold during their lives.

Resolving a clash between Homebrew and Python

22nd November 2022For reasons that I cannot recall now, I installed the Hugo static website generator on my Linux system and web servers using Homebrew. The only reason that I suggest is that it might have been a way to get the latest version at the time since Linux Mint only does major changes every two years, keeping it in line with long-term support editions of Ubuntu.

When Homebrew was installed, it changed the lookup path for command line executables by adding the following line to my .bashrc file:

eval "$(/home/linuxbrew/.linuxbrew/bin/brew shellenv)"

This executed the following lines:

export HOMEBREW_PREFIX="/home/linuxbrew/.linuxbrew";

export HOMEBREW_CELLAR="/home/linuxbrew/.linuxbrew/Cellar";

export HOMEBREW_REPOSITORY="/home/linuxbrew/.linuxbrew/Homebrew";

export PATH="/home/linuxbrew/.linuxbrew/bin:/home/linuxbrew/.linuxbrew/sbin${PATH+:$PATH}";

export MANPATH="/home/linuxbrew/.linuxbrew/share/man${MANPATH+:$MANPATH}:";

export INFOPATH="/home/linuxbrew/.linuxbrew/share/info:${INFOPATH:-}";

While the result suits Homebrew, it changed the setup of Python and its packages on my system. Eventually, this had undesirable consequences like messing up how Spyder started so I wanted to change this. There are other things that I have automated using Python and these were not working either.

One way that I have seen suggested is to execute the following command but I cannot vouch for this:

brew unlink python

What I did was to comment out the offending line in .bashrc and replace it with the following:

export PATH="$PATH:/home/linuxbrew/.linuxbrew/bin:/home/linuxbrew/.linuxbrew/sbin"

export HOMEBREW_PREFIX="/home/linuxbrew/.linuxbrew";

export HOMEBREW_CELLAR="/home/linuxbrew/.linuxbrew/Cellar";

export HOMEBREW_REPOSITORY="/home/linuxbrew/.linuxbrew/Homebrew";

export MANPATH="/home/linuxbrew/.linuxbrew/share/man${MANPATH+:$MANPATH}:";

export INFOPATH="${INFOPATH:-}/home/linuxbrew/.linuxbrew/share/info";

The first of these adds the Homebrew paths to the end of the PATH variable instead of the start of the same as was the case before. This means that system folders get searched for executable files before the Homebrew ones. It also means that Python packages are loaded from my user area and not the Homebrew one as was the case under its own terms. There are other things to remember with Python packages such as not having a version installed at the system level and another at the user one since these will conflict with one another.

So far, the result of the Homebrew changes is not unsatisfactory and I will watch for any rough edges that need addressing. If something comes up, then I will set things up in another way.

A desktop Markdown editing environment

8th November 2022Earlier this year, I changed over two websites from dynamic versions using content management systems to static ones by using Hugo to build them from Markdown files. That meant that I needed to look at the editing of MarkDown even if it is a fairly simple file format. For one thing, Grammarly can be incorporated into WordPress so I did not want to lose something like that.

The latter point meant that I was steered away from plain text editors. Otherwise, there are online ones like StackEdit and Dillinger but the Firefox Grammarly plugin only appears to work on the first of these, and even then only partially in my experience. Dillinger does offer connections to online file storage providers like Google, Dropbox and OneDrive but I wanted to store files on my desktop for upload to a web server. It also works with Github but I prefer to use another web hosting provider.

There are various specialised MarkDown editors for desktop usage like Typora, ReText, Formiko or Ghostwriter but I chose none of these. My actual choice may surprise many: it was Visual Studio Code. The availability of a Grammarly plug-in was what swayed it for me even if it did need to be switched on for MarkDown files. In many ways, it does work as smoothly as elsewhere because it gets fooled by links and other code-like pieces of text. Also, having the added ability to add words to a custom dictionary would be ideal. Some rule overriding is available but I am not sure that everything is covered even if the list of options is lengthy. Some time is needed to inspect all of them before I proceed any further. Thus far, things are working well enough for me.

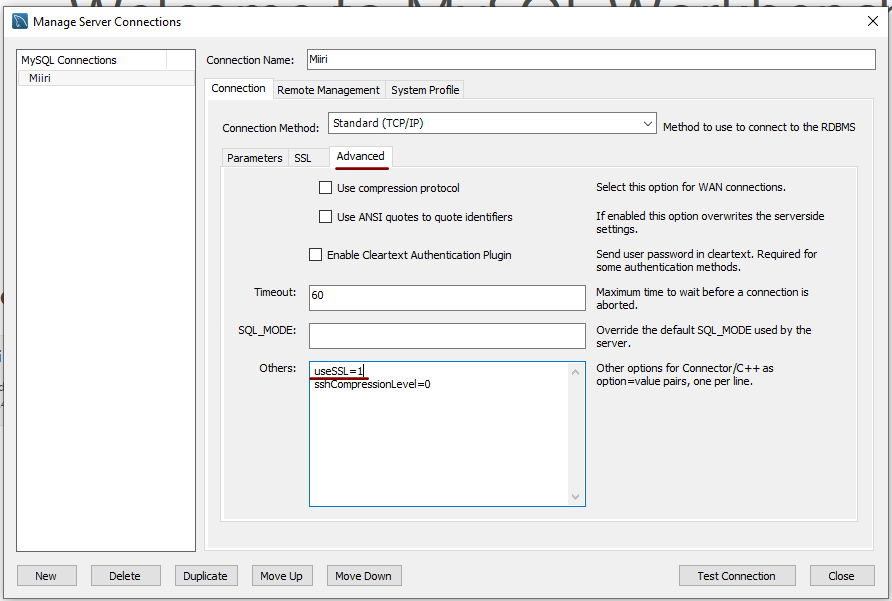

Disabling the SSL connection requirement in MySQL Workbench

7th November 2022A while ago, I found that MySQL Workbench would only use SSL connections and that was stopping it from connecting to local databases so I looked for a way to override this. The cure was to go to Database > Manage Connections… in the menus for the application’s home tab. in the dialogue box that appeared, I chose the connection of interest and went to the Advanced panel under Connection and removed the line useSSL=1 from the Others field. The screenshot below shows you what things look like before the change is made. Naturally, the best practice would be to secure a remote database connection using SSL so this approach is best reserved for remote non-production databases. However, it may be that this does not happen now but I thought I would share this in case the problem persists for anyone.