TOPIC: LIVE CD

Trying out a new way to upgrade Linux Mint in situ while going from 17.3 to 18.1

19th March 2017There was a time when the only recommended way to upgrade Linux Mint from one version to another was to do a fresh installation with back-ups of data and a list of the installed applications created from a special tool.

Even so, it never stopped me doing my own style of in situ upgrade, though some might see that as a risky option. More often than not, that actually worked without causing major problems in a time when Linux Mint releases were more tightly tied to Ubuntu's own six-monthly cycle.

Linux Mint releases now align with Ubuntu's Long Term Support (LTS) editions. This means major changes occur only every two years, with minor releases in between. These minor updates are delivered through Linux Mint's Update Manager, making the process simple. Upgrades are not forced, so you can decide when to upgrade, as all main and interim versions receive the same extended support. The recommendation is to avoid upgrading unless something is broken on your installation.

For a number of reasons, I stuck with that advice by sticking on my main machine with Linux Mint 17.3 instead of upgrading to Linux Mint 18. The fact that I broke things on another machine using an older method of upgrading provided even more encouragement.

However, I subsequently discovered another means of upgrading between major versions of Linux Mint that had some endorsement from the project. There still are warnings about testing a live DVD version of Linux Mint on your PC first and backing up your data beforehand. Another task is ensuring that you are upgraded from a fully up-to-date Linux Mint 17.3 installation.

When you are ready, you can install mintupgrade using the following command:

sudo apt-get install mintupgrade

When that is installed, there is a sequence of tasks that you need to do. The first of these is to simulate an upgrade to test for the appearance of untoward messages and resolve them. Repeating any checking, until all is well, gets a recommendation. The command is as follows:

mintupgrade check

Once you are happy that the system is ready, the next step is to download the updated packages so they are on your machine ahead of their installation. Only then should you begin the upgrade process. The two commands that you need to execute are below:

mintupgrade download

mintupgrade upgrade

After these complete, restart your system. In my case, the process worked well, with only my PHP installation requiring attention. I resolved a clash between different versions of the scripting interpreter by removing the older one, as PHP 7 is best kept for testing. Apart from reinstalling VMware Player and upgrading from version 18 to 18.1, I had almost nothing else to do and experienced minimal disruption. This is fortunate as I rely heavily on my main PC. The alternative of a full installation would have left me sorting things out for several days afterwards because I use a customised selection of software.

Compressing a VirtualBox VDI file for a Linux guest

6th June 2016In a previous posting, I talked about compressing a virtual hard disk for a Windows guest system running in VirtualBox on a Linux system. Since then, I have needed to do the same for a Linux guest following some housekeeping. Because the Linux distribution used is Debian, the instructions are relevant to that and maybe its derivatives such as Ubuntu, Linux Mint and their like.

While there are other alternatives like dd, I am going to stick with a utility named zerofree to overwrite the newly freed up disk space with zeroes to aid compression later on in the process for this and the first step is to install it using the following command:

apt-get install zerofree

Once that has been completed, the next step is to unmount the relevant disk partition. Luckily for me, what I needed to compress was an area that I reserved for synchronisation with Dropbox. If it was the root area where the operating system files are kept, a live distro would be needed instead. In any event, the required command takes the following form, with the mount point being whatever it is on your system (/home, for instance):

sudo umount [mount point]

With the disk partition unmounted, zerofree can be run by issuing a command that looks like this:

zerofree -v /dev/sdxN

Above, the -v switch tells zerofree to display its progress and a continually updating percentage count tells you how it is going. The /dev/sdxN piece is generic with the x corresponding to the letter assigned to the disk on which the partition resides (a, b, c or whatever) and the N is the partition number (1, 2, 3 or whatever; before GPT, the maximum was 4). Putting all this together, we get an example like /dev/sdb2.

Once, that had completed, the next step is to shut down the VM and execute a command like the following on the host Linux system ([file location/file name] needs to be replaced with whatever applies on your system):

VBoxManage modifyhd [file location/file name].vdi --compact

With the zero filling in place, there was a lot of space released when I tried this. While it would be nice for dynamic virtual disks to reduce in size automatically, I accept that there may be data integrity risks with those, so the manual process will suffice for now. It has not been needed that often anyway.

What I learned from manually upgrading to Linux Mint 11

31st May 2011For a Linux distribution that focuses on user-friendliness, it does surprise me that Linux Mint offers no seamless upgrade path. In fact, the underlying philosophy is that upgrading an operating system is a risky business. However, I have been doing in-situ upgrades with both Ubuntu and Fedora for a few years without any real calamities. A mishap with a hard drive that resulted in lost data in the days when I mainly was a Windows user places this into sharp relief. These days, I am far more careful but thought nothing of sticking a Fedora DVD into a drive to move my Fedora machine from 14 to 15 recently. Apart from a few rough edges and the need to get used to GNOME 3 together with making a better fit for me, there was no problem to report. The same sort of outcome used to apply to those online Ubuntu upgrades that I was accustomed to doing.

The recommended approach for Linux Mint is to back up your package lists and your data before the upgrade. Doing the former is a boon because it automates adding the extras that a standard CD or DVD installation doesn't do. While I did do a little backing up of data, it wasn't total because I know how to identify my drives and take my time over things. Apache settings and the contents of MySQL databases were my main concern because of where these are stored.

When I was ready to do so, I popped a DVD in the drive and carried out a fresh installation into the partition where my operating system files are kept. Being a Live DVD, I was able to set up any drive and partition mappings by referring to Mint's Disk Utility. One thing that didn't go so well was the GRUB installation, and it was due to the choice that I made on one of the installation screens. Despite doing an installation of version 10 just over a month ago, I had overlooked an intricacy of the task and placed GRUB on the operating system files partition rather than at the top level of the disk where it is located. Instead of trying to address this manually, I took the easier and more time-consuming step of repeating the installation like I did the last time. If there was a graphical tool for addressing GRUB problems, I might have gone for that instead, but am left wondering at why there isn't one included at all. Maybe it's something that the people behind GRUB should consider creating, unless there is one out there already about which I know nothing.

With the booting problem sorted, I tried logging in, only to find a problem with my desktop that made the system next to unusable. It was back to the DVD, and I moved many of the configuration files and folders (the ones with names beginning with a ".") from my home directory in the belief that there might have been an incompatibility. That action gained me a fully usable desktop environment, but I now think that the cause of my problem may have been different to what I initially suspected. Later I discovered that ownership of files in my home area elsewhere wasn't associated with my user ID, though there was no change to it during the installation. As it happened, a few minutes with the chown command were enough to sort out the permissions issue.

The restoration of the extra software that I had added beyond what standardly gets installed was took its share of time, but the use of a previously prepared list made things so much easier. That it didn't work smoothly because some packages couldn't be found the first time around, so another one was needed. Nevertheless, that is nothing compared to the effort needed to do the same thing by issuing an installation command at a time. Once the usual distribution software updates were in place, all that was left was to update VirtualBox to the latest version, install a Citrix client and add a PHP plugin to NetBeans. Then, nearly everything was in place for me.

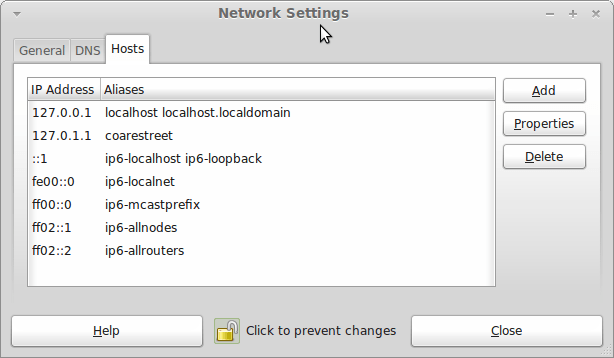

Next, Apache settings were restored, as were the databases that I used for offline web development. That nearly was all that was needed to get offline websites working, but for the need to add an alias for localhost.localdomain. That required installation of the Network Settings tool so that I could add the alias in its Hosts tab. With that out of the way, the system had been settled in and was ready for real work.

Given the glitches I encountered, I can understand the Linux Mint team's caution regarding a more automated upgrade process. Even so, I still wonder if the more manual alternative that they have pursued brings its own problems in the form of those that I met. The fact that the whole process took a few hours in comparison to the single hour taken by the in-situ upgrades that I mentioned earlier is another consideration that makes you wonder if it is all worth it every six months or so. Saying that, there is something to letting a user decide when to upgrade rather than luring one along to a new version, a point that is more than pertinent in light of the recent changes made to Ubuntu and Fedora. Whichever approach you care to choose, there are arguments in favour as well as counterarguments too.

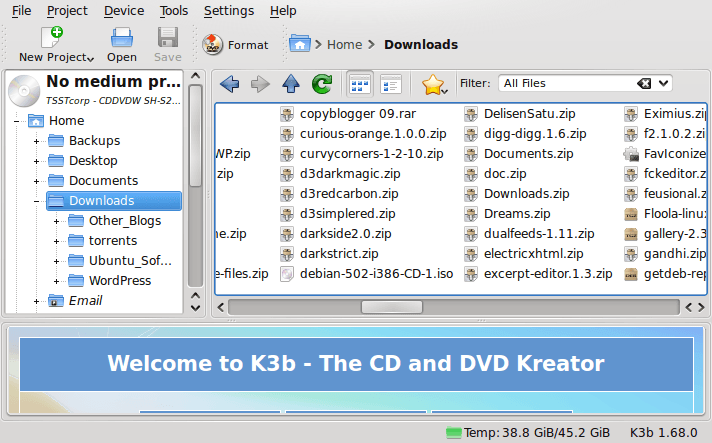

A use for choice

8th November 2009After moving to Ubuntu 9.10, Brasero stopped behaving as well as it did in Ubuntu 9.04. Any bootable disks that I have created with it weren't without glitches. After a recent update, things got better with a live CD actually booting up a PC rather than failing to find a file system like those created with its forbear. While unsure if the observed imperfections stemmed from my using the RC for the upgrades and installations, I got to looking for a solution and gave K3b a go. It certainly behaves like I'd expect it, and a live CD created with it worked without fault. The end result is that Brasero has been booted off my main home system for now. That may mean that all the in-built GNOME convenience is lost to me, but I can live without the extras; after all, it's the quality of the created disks that matters.

Booting from external drives

16th September 2009Sticking with older hardware may mean that you miss out on the possibilities offered by later kit, and being able to boot from external optical and hard disk drives was something of which I learned only recently. Like many things, a compatible motherboard and my enforced summer upgrade means that I have one with the requisite capabilities.

There is usually an external DVD drive attached to my main PC, so that allowed the prospect of a test. A bit of poking around in the BIOS settings for the Foxconn motherboard was sufficient to get it looking at the external drive at boot time. Popping in a CrunchBang Linux live DVD was all that was needed to prove that booting from a USB drive was a goer. That CrunchBang is a minimalist variant of Ubuntu helped for acceptable speed at system startup and afterwards.

Having lived off them while in home PC limbo, the temptation to test out the idea of installing an operating system on an external HD and booting from that is definitely there, though I think that I'll be keeping mine as backup drives for now. Still, there's nothing to stop me installing an operating system onto of them and giving that a whirl sometime. Of course, speed constraints mean that any use of such an arrangement would be occasional but, in the event of an emergency, such a setup could have its uses and tide you over for longer than a Live CD or DVD. Having the chance to poke around with an alternative operating system as it might exist on a real PC has its appeal too, and avoids the need for any partitioning and other chores that dual booting would require. After all, there's only so much testing that can be done in a virtual machine.

Choices, choices…

10th November 2007While choice is a great thing, too much of it can be confusing, and the world of Linux is a one very full of decisions. The first of these centres around the distro to use when taking the plunge; you quickly find that there can be quite a lot to it. In fact, it is a little like buying your first SLR/DSLR or your first car: you only really know what you are doing after your first one. Putting it another way, you only know how to get a house built after you have done just that.

With that in mind, it is probably best to play a little on the fringes of the Linux world before committing yourself. It used to be that you had two main choices for your dabbling:

- using a spare PC

- dual booting with Windows by either partitioning a hard drive or dedicating one for your Linux needs.

In these times, innovations such as Live CD distributions and virtualisation technology keep you away from such measures. In fact, I would suggest starting with the former and progressing to the latter for more detailed perusal; it's always easy to wipe and restore virtual machines anyway, so you can evaluate several distros at the same time if you have the hard drive space. It also a great way to decide which desktop environment you like. Otherwise, terms like KDE, GNOME, XFCE, etc. might not mean much.

The mention of desktop environments brings me to software choices because they do drive what software is available to you. For instance, the Outlook lookalike that is Evolution is more likely to appear where GNOME is installed than where you have KDE. The opposite applies to the music player Amarok. Nevertheless, you do find certain stalwarts making a regular appearance; Firefox, OpenOffice and the GIMP all fall into this category.

The nice thing about Linux is that distros more often than not contain all the software that you are likely to need. However, that doesn't mean that it is all on the disk and that you have to select what you need during the installation. Though there might have been a time when it might have felt like that, my recent experience has been that a minimum installation is set in place that does all the basics for you to easily add the extras later on an as needed basis. I have also found that online updates are a strong feature too.

Picking up what you need when you need it has major advantages, the big one being that Linux grows with you. You can add items like Apache, PHP and MySQL when you know what they are and why you need them. It's a long way from picking applications of which you know very little at installation time and with the suspicion that any future installation might land you in dependency hell while performing compilation of application source code; the temptation to install everything that you saw was a strong one. The "learn before you use" approach favoured by how things are done nowadays is an excellent one.

Even if life is easier in the Linux camp these days, there is no harm in sketching out your software needs. Any distribution should be able to fulfil most if not all of them. As it happened, the only third party application that I have needed to install on Ubuntu without recourse to Synaptic was VMware Workstation, and that procedure thankfully turned out to be pretty painless.