TOPIC: ADOBE

Latest developments in the AI landscape: Consolidation, implementation and governance

22nd November 2025Artificial intelligence is moving through another moment of consolidation and capability gain. New ways to connect models to everyday tools now sit alongside aggressive platform plays from the largest providers, a steady cadence of model upgrades, and a more defined conversation about risk and regulation. For companies trying to turn all this into practical value, the story is becoming less about chasing the latest benchmark and more about choosing a platform, building the right connective tissue, and governing data use with care. The coming year looks set to reward those who simplify the user experience, embed AI directly into work and adopt proportionate controls rather than blanket bans.

I. Market Structure and Competitive Dynamics

Platform Consolidation and Lock-In

Enterprise AI appears to be settling into a two-platform market. Analysts describe a landscape defined more by integration and distribution than raw model capability, evoking the cloud computing wars. On one side sit Microsoft and OpenAI, on the other Google and Gemini. Recent signals include the pricing of Gemini 3 Pro at around two dollars per million tokens, which undercuts much of the market, Alphabet's share price strength, and large enterprise deals for Gemini integrated with Google's wider software suite. Google is also promoting Antigravity, an agent-first development environment with browser control, asynchronous execution and multi-agent support, an attempt to replicate the pull of VS Code within an AI-native toolchain.

The implication for buyers is higher switching costs over time. Few expect true multi-cloud parity for AI, and regional splits will remain. Guidance from industry commentators is to prioritise integration across the existing estate rather than incremental model wins, since platform choices now look like decade-long commitments. Events lined up for next year are already pointing to that platform view.

Enterprise Infrastructure Alignment

A wider shift in software development is also taking shape. Forecasts for 2026 emphasise parallel, multi-agent systems where a planning agent orchestrates a set of execution agents, and harnesses tune themselves as they learn from context. There is growing adoption of a mix-of-models approach in which expensive frontier models handle planning, and cheaper models do the bulk of execution, bringing near-frontier quality for less money and with lower latency. Team structures are changing as a result, with more value placed on people who combine product sense with engineering craft and less on narrow specialisms.

ServiceNow and Microsoft have announced a partnership to coordinate AI agents across organisations with tighter oversight and governance, an attempt to avoid the sprawl that plagued earlier automation waves. Nvidia has previewed Apollo, a set of open AI physics models intended to bring real-time fidelity to simulations used in science and industry. Albania has appointed an AI minister, which has kicked off debate about how governments should manage and oversee their own AI use. CIOs are being urged to lead on agentic AI as systems become capable of automating end-to-end workflows rather than single steps.

New companies and partnerships signal where capital and talent are heading. Jeff Bezos has returned to co-lead Project Prometheus, a start-up with $6.2 billion raised and a team of about one hundred hires from major labs, focused on AI for engineering and manufacturing in the physical world, an aim that aligns with Blue Origin interests. Vik Bajaj is named as co-CEO.

Deals underline platform consolidation. Microsoft and Nvidia are investing up to $5 billion and $10 billion respectively (totalling $15 billion) in Anthropic, whilst Anthropic has committed $30 billion in Azure capacity purchases with plans to co-design chips with Nvidia.

Commercial Model Evolution

Events and product launches continue at pace. xAI has released Grok 4.1 with an emphasis on creativity and emotional intelligence while cutting hallucinations. On the tooling front, tutorials explain how ChatGPT's desktop app can record meetings for later summarisation. In a separate interview, DeepMind's Demis Hassabis set out how Gemini 3 edges out competitors in many reasoning and multimodal benchmarks, slightly trails Claude Sonnet 4.5 in coding, and is being positioned for foundations in healthcare and education though not as a medical-grade system. Google is encouraging developers towards Antigravity for agentic workflows.

Industry leaders are also sketching commercial models that assume more agentic behaviour, with Microsoft's Satya Nadella promising a "positive-sum" vision for AI while hinting at per-agent pricing and wider access to OpenAI IP under Microsoft's arrangements.

II. Technical Implementation and Capability

Practical Connectivity Over Capability

A growing number of organisations are starting with connectors that allow a model to read and write across systems such as Gmail, Notion, calendars, CRMs, and Slack. Delivered via the Model Context Protocol, these links pull the relevant context into a single chat, so users spend less time switching windows and more time deciding what to do. Typical gains are in hours saved each week, lower error rates, and quicker responses. With a few prompts, an assistant can draft executive email summaries, populate a Notion database with leads from scattered sources, or propose CRM follow-ups while showing its working.

The cleanest path is phased: enable one connector using OAuth, trial it in read-only mode, then add simple routines for briefs, meeting preparation or weekly reports before switching on write access with a "show changes before saving" step. Enterprise controls matter here. Connectors inherit user permissions via OAuth 2.0, process data in memory, and vendors point to SOC 2, GDPR and CCPA compliance alongside allow and block lists, policy management, and audit logs. Many governance teams prefer to begin read-only and require approvals for writes.

There are limits to note, including API rate caps, sync delays, context window constraints and timeouts for long workflows. They are poor fits for classified data, considerable bulk operations or transactions that cannot tolerate latency. Some industry observers regard Claude's current MCP implementation, particularly on desktop, as the most capable of the group. Playbooks for a 30-day rollout are beginning to circulate, as are practitioner workshops introducing go-to-market teams to these patterns.

Agentic Orchestration Entering Production

Practical comparisons suggest the surrounding tooling can matter more than the raw model for building production-ready software. One report set a 15-point specification across several environments and found that Claude Code produced all features end-to-end. The same spec built with Gemini 3 inside Antigravity delivered two thirds of the features, while Sonnet 4.5 in Antigravity delivered a little more than half, with omissions around batching, progress indicators and robust error handling.

Security remains a live issue. One newsletter reports that Anthropic said state-backed Chinese hackers misused Claude to autonomously support a large cyberattack, which has intensified calls for governance. The background hum continues, from a jump in voice AI adoption to a German ruling on lyric copyright involving OpenAI, new video guidance steps in Gemini, and an experimental "world model" called Marble. Tools such as Yorph are receiving attention for building agentic data pipelines as teams look to productionise these patterns.

Tooling Maturity Defining Outcomes

In engineering practice, Google's Code Wiki brings code-aware documentation that stays in sync with repositories using Gemini, supported by diagrams and interactive chat. GitLab's latest survey suggests AI increases code creation but also pushes up demand for skilled engineers alongside compliance and human oversight. In operations, Chronosphere has added AI remediation guidance to cut observability noise and speed root-cause analysis while performance testing is shifting towards predictive, continuous assurance rather than episodic tests.

Vertical Capability Gains

While the platform picture firms up, model and product updates continue at pace. Google has drawn attention with a striking upgrade to image generation, based on Gemini 3. The system produces 4K outputs with crisp text across multiple languages and fonts, can use up to 14 reference images, preserves identity, and taps Google Search to ground data for accurate infographics.

Separately, OpenAI has broadened ChatGPT Group Chats to as many as 20 people across all pricing tiers, with privacy protections that keep group content out of a user's personal memory. Consumer advocates have used the moment to call out the risks of AI toys, citing safety, privacy and developmental concerns, even as news continues to flow from research and product teams, from the release of OLMo 3 to mobile features from Perplexity and a partnership between Stability and Warner Music Group.

Anthropic has answered with Claude Opus 4.5, which it says is the first model to break the 80 percent mark on SWE-Bench Verified while improving tool use and reasoning. Opus 4.5 is designed to orchestrate its smaller Haiku models and arrives with a price cut of roughly two thirds compared to the 4.1 release. Product changes include unlimited chat length, a Claude Code desktop app, and integrations that reach across Chrome and Excel.

OpenAI's additions have a more consumer flavour, with a Shopping Research feature in ChatGPT that produces personalised product guidance using a GPT-5 mini variant and plans for an Instant Checkout flow. In government, a new US executive order has launched the "Genesis Mission" under the Department of Energy, aiming to fuse AI capabilities across 17 national labs for advances in fields such as biotechnology and energy.

Coding tools are evolving too. OpenAI has previewed GPT-5.1-Codex-Max, which supports long-running sessions by compacting conversational history to preserve context while reducing overhead. The company reports 30 percent fewer tokens and faster performance over sessions that can run for more than a day. The tool is already available in the Codex CLI and IDE, with an API promised.

Infrastructure news out of the Middle East points to large-scale investment, with Saudi HUMAIN announcing data centre plans including xAI's first international facility alongside chips from Nvidia and AWS, and a nationwide rollout of Grok. In computer vision, Meta has released SAM 3 and SAM 3D as open-source projects, extending segmentation and enabling single-photo 3D reconstruction, while other product rollouts continue from GPT-5.1 Pro availability to fresh funding for audio generation and a marketing tie-up between Adobe and Semrush.

On the image side, observers have noted syntax-aware code and text generation alongside moderation that appears looser than some rivals. A playful "refrigerator magnet" prompt reportedly revealed a portion of the system prompt, a reminder that prompt injection is not just a developer concern.

Video is another area where capabilities are translating into business impact. Sora 2 can generate cinematic, multi-shot videos with consistent characters from text or images, which lets teams accelerate marketing content, broaden A/B testing and cut the need for studios on many projects. Access paths now span web, mobile, desktop apps and an API, and the market has already produced third-party platforms that promise exports without watermarks.

Teams experimenting with Sora are being advised to measure success by outcomes such as conversion rates, lower support loads or improved lead quality rather than just aesthetic fidelity. Implementation advice favours clear intent, structured prompts and iterative variation, with more advanced workflows assembling multi-shot storyboards, using match cuts to maintain rhythm, controlling lighting for continuity and anchoring character consistency across scenes.

III. Governance, Risk and Regulation

Governance as a Product Requirement

Amid all this activity, data risk has become a central theme for AI leaders. One governance specialist has consolidated common problem patterns into the PROTECT framework, which offers a way to map and mitigate the most material risks.

The first concern is the use of public AI tools for work content, which raises the chance of leakage or unwanted training on proprietary data. The recommended answer combines user guidance, approved internal alternatives, and technical or legal controls such as data scanning and blocking.

A second pressure point is rogue internal projects that bypass review, create compliance blind spots and build up technical debt. Proportionate oversight is key, calibrated to data sensitivity and paired with streamlined governance, so teams are not incentivised to route around it.

Third-party vendors can be opportunistic with data, so due diligence and contractual clauses need to prevent cross-customer training and make expectations clear with templates and guidance.

Technical attacks are another strand, from prompt injection to data exfiltration or the misuse of agents. Layered defences help here, including input validation, prompt sanitisation, output filtering, monitoring, red-teaming, and strict limits on access and privilege.

Embedded assistants and meeting bots come with permission risks when they operate over shared drives and channels, and agentic systems can amplify exposure if left unchecked, so the advice is to enforce least-privilege access, start on low-risk data, and keep robust audit trails.

Compliance risks span privacy laws such as GDPR with their demands for a lawful basis, IP and copyright constraints, contractual obligations, and the AI Act's emphasis on data quality. Legal and compliance checks need to be embedded at data sourcing, model training and deployment, backed by targeted training.

Finally, cross-border restrictions matter. Transfers should be mapped across systems and sub-processors, with checks for Data Privacy Framework certification, standard contractual clauses where needed, and transfer impact assessments that take account of both GDPR and newer rules such as the US Bulk Data Transfer Rule.

Regulatory Pragmatism

Regulators are not standing still, either. In the European Commission has proposed amendments to the AI Act through a Digital Omnibus package as the trilogue process rolls on. Six changes are in focus:

- High-risk timelines would be tied to the approval of standards, with a backstop of December 2027 for Annex III systems and August 2028 for Annex I products if delays continue, though the original August 2026 date still holds otherwise.

- Transparency rules on AI-detectable outputs under Article 50(2) would be delayed to February 2027 for systems placed on the market before August 2026, with no delay for newer systems.

- The plan removes the need to register Annex III systems in the public database where providers have documented under Article 6(3) that a system is not high risk.

- AI literacy would shift from a mandatory organisation-wide requirement to encouragement, except where oversight of high-risk systems demands it.

- There is also a move to centralise supervision by the AI Office for systems built on general-purpose models by the same provider, and for huge online platforms and search engines, which is intended to reduce fragmentation across member states.

- Finally, proportionality measures would define Small Mid-Cap companies and extend simplified obligations and penalty caps that currently apply to SMEs.

If adopted, the package would grant more time and reduce administrative load in some areas, at the expense of certainty and public transparency.

IV. Strategic Implications

The picture that emerges is one of pragmatic integration. Connectors make it feasible to keep work inside a single chat while drawing on the systems people already use. Platform choices are converging, so it makes sense to optimise for the suite that fits the current stack and to plan for switching costs that accumulate over time.

Agentic orchestration is moving from slides to code, but teams will get further by focusing on reliable tooling, clear governance and value measures that match business goals. Regulation is edging towards more flexible timelines and centralised oversight in places, which may lower administrative load without removing the need for discipline.

The sensible posture is measured experimentation: start with read-only access to lower-risk data, design routines that remove drudgery, introduce write operations with approvals, and monitor what is actually changing. The tools are improving quickly, yet the organisations that benefit most will be those that match innovation with proportionate controls and make thoughtful choices now that will hold their shape for the decade ahead.

AI infrastructure under pressure: Outages, power demands and the race for resilience

1st November 2025The past few weeks brought a clear message from across the AI landscape: adoption is racing ahead, while the underlying infrastructure is working hard to keep up. A pair of major cloud outages in October offered a stark stress test, exposing just how deeply AI has become woven into daily services.

At the same time, there were significant shifts in hardware strategy, a wave of new tools for developers and creators and a changing playbook for how information is found online. There is progress on resilience and efficiency, yet the system is still bending under demand. Understanding where it held, where it creaked and where it is being reinforced sets the scene for what comes next.

Infrastructure Stress and Outages

The outages dominated early discussion. An AWS incident that lasted around 15 hours and disrupted more than a thousand services was followed nine days later by a global Azure failure. Each cascaded across systems that depend on them, illustrating how AI now amplifies the consequences of platform problems.

This was less about a single point of failure and more about the growing blast radius when connected services falter. The effect on productivity was visible too: a separate 10-hour ChatGPT downtime showed how fast outages of core AI tools now translate into lost work time.

Power Demand and Grid Strain

Behind the headlines sits a larger story about electricity, grids and planning. Data centres accounted for roughly 4% of US electricity use in 2024, about 183 TWh and the International Energy Agency projects around 945 TWh by 2030, with AI as a principal driver.

The averages conceal stark local effects. Wholesale prices near dense clusters have spiked by as much as 267% at times, household bills are rising by about $16–$18 per month in affected areas and capacity prices in the PJM market jumped from $28.92 per megawatt to $329.17. The US grid faces an upgrade bill of about $720 billion by 2030, yet permitting and build timelines are long, creating a bottleneck just as demand accelerates.

Technical Grid Issues

Technical realities on the grid add another layer of challenge. Fast load swings from AI clusters, harmonic distortions and degraded power quality are no longer theoretical concerns. A Virginia incident in which 60 data centres disconnected simultaneously did not trigger a collapse but did reveal the fragility introduced by concentrated high-performance compute.

Security and New Failure Modes

Security risks are evolving in parallel. Agentic systems that can plan, reason and call tools open new failure modes. AI-enabled spear phishing appears to be 350% more effective than traditional attempts and could be 50 times more profitable, a worrying backdrop when outages already have a clear link to lost productivity.

Security considerations now reach into the tools people use to access AI as well. New AI browsers attract attention, and with that comes scrutiny. OpenAI's Atlas and Perplexity's Comet launched with promising features, yet researchers flagged critical issues.

Comet is vulnerable to "CometJacking", a malicious URL hijack that enables data theft, while Atlas suffered a cross-site request forgery weakness that allowed persistent code injection into ChatGPT memory. Both products have been noted for assertive data collection.

Caution and good hygiene are prudent until the fixes and policies settle. It is a reminder that the convenience of integrating models directly into browsing comes with a new attack surface.

Efficiency and Mitigation Strategies

Industry responses are gathering pace. Efficiency remains the first lever. Hyperscalers now report power usage effectiveness around 1.08 to 1.09, compared with more typical figures of 1.5 to 1.6. Direct chip cooling can cut energy needs by up to 40%.

Grid-interactive operations and more work at the edge offer ways to smooth demand and reduce concentration risk, while new power partnerships hint at longer-term change. Microsoft's agreement with Constellation on nuclear power is one example of how compute providers are thinking beyond incremental efficiency gains.

An emerging pattern is becoming visible through these efforts. Proactive regional planning and rapid efficiency improvements could allow computational output to grow by an order of magnitude, while power use merely doubles. More distributed architectures are being explored to reduce the hazard of over-concentration.

A realistic outlook sets data centres at around 3% of global electricity use by 2030, which is notable but still smaller than anticipated growth from electric vehicles or air conditioning. If the $720 billion in grid investment materialises, it could add around 120 GW of capacity by 2030, as much as half of which would be absorbed by data centres. The resilience gap is real, but it appears to be narrowing, provided the sector moves quickly to apply lessons from each failure.

Regional and Policy Responses

Regional policies are starting to encourage resilience too. Oregon's POWER Act asks operators to contribute to grid robustness, Singapore's tight focus on efficiency has delivered around a 30% power reduction even as capacity expands and a moratorium in Dublin has pushed growth into more distributed build-outs. On the U.S. federal government side, the Department of Homeland Security updated frameworks after a 2024 watchdog warning, with AI risk programmes now in place for 15 of the 16 critical infrastructure sectors.

Hardware Competition and Strategy

Competition is sharpening. Anthropic deepened its partnership with Google Cloud to train on TPUs, a move that challenges Nvidia's dominance and signals a broader rebalancing in AI hardware. Nvidia's chief executive has acknowledged TPUs as robust competition.

Another fresh entry came from Extropic, which unveiled thermodynamic sampling units, a probabilistic chip design that claims up to 10,000-fold lower energy use than GPUs for AI workloads. Development kits are shipping and a Z-1 chip is planned for next year, yet as with any radical architecture, proof at scale will take time.

Nvidia, meanwhile, presented an ambitious outlook, targeting $500 billion in chip revenue by 2026 through its Blackwell and Rubin lines. The US Department of Energy plans seven supercomputers comprising more than 100,000 Blackwell GPUs and the company announced partnerships spanning pharmaceuticals, industrials and consumer platforms.

A $1 billion investment in Nokia hints at the importance of AI-centric networks. New open-source models and datasets accompanied the announcements, and the company's share price surged to a record.

Corporate Restructuring

Corporate strategy and hardware choices also entered a new phase. OpenAI completed its restructuring into a public benefit corporation, with a rebranded OpenAI Foundation holding around $130 billion in equity and allocating $25 billion to health and AI resilience. Microsoft's stake now sits at about 27% and is worth roughly $135 billion, with technology rights retained through 2032. Both parties have scope to work with other partners. OpenAI committed around $250 billion to Azure yet retains the ability to use other compute providers. An independent panel will verify claims of artificial general intelligence, an unusual governance step that will be watched closely.

Search and Discovery Evolution

Away from infrastructure, the way audiences find and trust information is shifting. Search is moving from the old aim of ranking for clicks to answer engine optimisation, where the goal is to be quoted by systems such as ChatGPT, Claude or Perplexity.

The numbers explain why. Google handled more than five trillion queries in 2024, while generative platforms now process around 37.5 million prompt-like searches per day. Google's AI Overviews, which surface summary answers above organic results, have reshaped click behaviour.

Independent analyses report top-ranking pages seeing click-through rates fall by roughly a third where Overviews appear, with some keywords faring worse, and a Pew study finds overall clicks on such results dropping from 15% to 8%. Zero-click searches rose from around 56% to 69% between May 2024 and May 2025.

Chegg's non-subscriber traffic fell by 49% in this period, part of an ongoing dispute with Google. Google counters that total engagement in covered queries has risen by about 10%. Whichever way that one reads the data, the direction is clear: visibility is less about rank position and more about being cited by a summarising engine.

In practice, that means structuring content, so a model can parse, trust and attribute it. Clear Q&A-style sections with direct answers, followed by context and cited evidence, help models extract usable statements. Schema markup for FAQs and how-to content improves machine readability.

Measuring success also changes. Traditional analytics rarely show when an LLM quotes a source, so teams are turning to tools that track citations in AI outputs and tying those to conversion quality, branded search volume and more in-depth engagement with pricing or documentation. It is not a replacement for SEO so much as a layer that reinforces it in an AI-first environment.

Developer Tools and Agentic Workflows

On the tools front, developers saw an acceleration in agent-centred workflows. Cursor launched its first in-house coding model, Composer, which aims for near-frontier quality while generating code around four times faster, often in under 30 seconds.

The broader Cursor 2.0 update added multi-agent capabilities, with as many as eight assistants able to work in parallel, alongside browsing, a test browser and voice controls. The direction of travel is away from single-shot completions and towards orchestration and review. Tutorials are following suit, demonstrating how to scaffold tasks such as a Next.js to-do application using planning files, parallel agent tasks and quick integration, with voice prompts in the loop.

Open-source and enterprise ecosystems continue to expand. GitHub introduced Agent HQ for coordinating coding agents, Google released Pomelli to generate marketing campaigns and IBM's Granite 4.0 Nano models brought larger on-device options in the 350 million to 1.5 billion parameter range.

FlowithOS reported strong scores on agentic web tasks, while Mozilla announced an open speech dataset initiative, and Kilo Code, Hailuo 2.3 and other projects broadened choice across coding and video. Grammarly rebranded as Superhuman, adding "Superhuman Go" agents to speed up writing tasks.

Creative Tools and Partnerships

Creative workflows are evolving quickly, too. Adobe used its MAX event to add AI assistants to Photoshop and Express, previewed an agent called Project Moonlight, and upgraded Firefly with conversational "Prompt to Edit" controls, custom image models and new video features including soundtracks and voiceovers. Partnerships mean Gemini, Veo and Imagen will sit inside Adobe tools, and Premiere's editing capabilities now extend to YouTube Shorts.

Figma acquired Weavy and rebranded it as Figma Weave for richer creative collaboration, and Canva unveiled its own foundation "Design Model" alongside a Creative Operating System meant to produce fully editable, AI-generated designs. New Canva features take in a revised video suite, forms, data connectors, email design, a 3D generator and an ad creation and performance tool called Grow, while Affinity is relaunching as a free, integrated professional app. Other entrants are trying to blend model strengths: one agent was trailed with Sora 2 clip stitching, Veo 3.1 visuals and multimodel blending for faster design output.

Music rights and AI found a new footing. Universal Music Group settled a lawsuit with Udio, the AI music generator, and the two will form a joint venture to launch a licensed platform in 2026. Artists who opt in will be paid both for training models on their catalogues and for remixes. Udio disabled song downloads following the deal, which annoyed some users, and UMG also announced a "responsible AI" alliance with Stability AI to build tools for artists. These arrangements suggest a path towards sanctioned use of style and catalogue, with compensation built in from the start.

Research and Introspection

Research and science updates added depth. Anthropic reported that its Claude system shows limited introspection, detecting planted concepts only about 20% of the time, separating injected "thoughts" from text and modulating its internal focus. That highlights both the promise and limits of transparency techniques, and the potential for models to conceal or fail to surface certain internal states.

UC Berkeley researchers demonstrated an AI-driven load balancing algorithm with around 30% efficiency improvements, a result that could ripple through cloud performance. IBM ran quantum algorithms on AMD FPGAs, pointing to progress in hybrid quantum-classical systems.

OpenAI launched an AI-integrated web browser positioned as a challenger to incumbents, Perplexity released a natural-language patents search and OpenAI's Aardvark, a GPT-5-based security agent, entered private beta.

Anthropic opened a Tokyo office and signed a cooperation pact with Japan's AI Safety Institute. Tether released QVAC Genesis I, a large open STEM dataset of more than one million data points and a local workbench app aimed at making development more private and less dependent on big platforms.

Age Restrictions and Policy

Meanwhile, policy considerations are reaching consumer platforms. Character AI will restrict users under 18 from open-ended chatbot conversations from late November, replacing them with creative tools and adding behaviour-based age detection, a response to pressure and proposals such as the GUARD Act.

Takeaways

Put together, the picture is one of rapid interdependence and swift correction. The infrastructure is not breaking, but it is being stretched, and recent failures have usefully mapped the weak points. If the sector continues to learn quickly from its own missteps, the resilience gap will continue to narrow, and the next round of outages will be less disruptive than the last.

Investment is flowing into grids and cooling, policy is nudging towards resilience, and compute providers are hedging hardware bets by searching for efficiency and supply assurance. On the application layer, agents are becoming a primary interface for work, creative tools are converging around editability and control, and discovery is shifting towards being quoted by machines rather than clicked by humans.

Security lapses at the interface are a reminder that novelty often arrives before maturity. The most likely path from here is uneven but forward: data centre power may rise, yet efficiency and distribution can blunt the impact; answer engines may compress clicks, yet they can send higher intent visitors to clear, well-structured sources; hardware competition may fragment the stack, yet it can also reduce concentration risk.

A snapshot of the current state of AI: Developments from the last few weeks

22nd August 2025A few unsettled days earlier in the month may have offered a revealing snapshot of where artificial intelligence stands and where it may be heading. OpenAI’s launch of GPT‑5 arrived to high expectations and swift backlash, and the immediate aftermath said as much about people as it did about technology. Capability plainly matters, but character, control and continuity are now shaping adoption just as strongly, with users quick to signal what they value in everyday interactions.

The GPT‑5 debut drew intense scrutiny after technical issues marred day one. An autoswitcher designed to route each query to the most suitable underlying system crashed at launch, making the new model appear far less capable than intended. A live broadcast compounded matters with a chart mishap that Sam Altman called a “mega chart screw‑up”, while lower than expected rate limits irritated early users. Within hours, the mood shifted from breakthrough to disruption of familiar workflows, not least because GPT‑5 initially displaced older options, including the widely used GPT‑4o. The discontent was not purely about performance. Many had grown accustomed to 4o’s conversational tone and perceived emotional intelligence, and there was a sense of losing a known counterpart that had become part of daily routines. Across forums and social channels, people described 4o as a model with which they had formed a rapport that spanned routine work and more personal support, with some comparing the loss to missing a colleague. In communities where AI relationships are discussed, engagement to chatbot companions and the influence of conversational style, memory for context and affective responses on day‑to‑day reliance came to the fore.

OpenAI moved quickly to steady the situation. Altman and colleagues fielded questions on Reddit to explain failure modes, pledged more transparency, and began rolling out fixes. Rate limits for paid tiers doubled, and subsequent changes lifted the weekly allowance for advanced reasoning from 200 “thinking” messages to 3,000. GPT‑4o returned for Plus subscribers after a flood of requests, and a “Show Legacy Models” setting surfaced so that subscribers could select earlier systems, including GPT‑4o and o3, rather than be funnelled exclusively to the newest release. The company clarified that GPT‑5’s thinking mode uses a 196,000‑token context window, addressing confusion caused by a separate 32,000 figure for the non‑reasoning variant, and it explained operational modes (Auto, Fast and Thinking) more clearly. Pricing has fallen since GPT‑4’s debut, routing across multiple internal models should improve reliability, and the system sustains longer, multi‑step work than prior releases. Even so, the opening days highlighted a delicate balance. A large cohort prioritised tone, the length and feel of responses, and the possibility of choice as much as raw performance. Altman hinted at that direction too, saying the real learning is the need for per‑user customisation and model personality, with a personality update promised for GPT‑5. Reinstating 4o underlined that the company had read the room. Test scores are not the only currency that counts; products, even in enterprise settings, become useful through the humans who rely on them, and those humans are making their preferences known.

A separate dinner with reporters extended the view. Altman said he “legitimately just thought we screwed that up” on 4o’s removal, and described GPT‑5 as pursuing warmer responses without being sycophantic. He also said OpenAI has better models it cannot offer yet because of compute constraints, and spoke of spending “trillions” on data centres in the near future. The comments acknowledged parallels with the dot‑com bubble (valuations “insane”, as he put it) while arguing that the underlying technology justifies massive investments. He added that OpenAI would look at a browser acquisition like Chrome if a forced sale ever materialised, and reiterated confidence that the device project with Jony Ive would be “worth the wait” because “you don’t get a new computing paradigm very often.”

While attention centred on one model, the wider tool landscape moved briskly. Anthropic rolled out memory features for Claude that retrieve from prior chats only when explicitly requested, a measured stance compared with systems that build persistent profiles automatically. Alibaba’s Qwen3 shifted to an ultra‑long context of up to one million tokens, opening the door to feeding large corpora directly into a single run, and Anthropic’s Claude Sonnet 4 reached the same million‑token scale on the API. xAI offered Grok 4 to a global audience for a period, pairing it with an image long‑press feature that turns pictures into short videos. OpenAI’s o3 model swept a Kaggle chess tournament against DeepSeek R1, Grok‑4 and Gemini 2.5 Pro, reminding observers that narrowly defined competitions still produce clear signals. Industry reconfigured in other corners too. Microsoft folded GitHub more tightly into its CoreAI group as the platform’s chief executive announced his departure, signalling deeper integration across the stack, and the company introduced Copilot 3D to generate single‑click 3D assets. Roblox released Sentinel, an open model for moderating children’s chat at scale. Elsewhere, Grammarly unveiled a set of AI agents for writing tasks such as citations, grading, proofreading and plagiarism checks, and Microsoft began testing a new COPILOT function in Excel that lets users generate summaries, classify data and create tables using natural language prompts directly in cells, with the caveat that it should not be used in high‑stakes settings yet. Adobe likewise pushed into document automation with Acrobat Studio and “PDF Spaces”, a workspace that allows people to summarise, analyse and chat about sets of documents.

Benchmark results added a different kind of marker. OpenAI’s general‑purpose reasoner achieved a gold‑level score at the 2025 International Olympiad in Informatics, placing sixth among human contestants under standard constraints. Reports also pointed to golds at the International Mathematical Olympiad and at AtCoder, suggesting transfer across structured reasoning tasks without task‑specific fine‑tuning and a doubling of scores year-on-year. Scepticism accompanied the plaudits, with accounts of regressions in everyday coding or algebra reminding observers that competition outcomes, while impressive, are not the same thing as consistent reliability in daily work. A similar duality followed the agentic turn. ChatGPT’s Agent Mode, now more widely available, attempts to shift interactions from conversational turns to goal‑directed sequences. In practice, a system plans and executes multi‑step tasks with access to safe tool chains such as a browser, a code interpreter and pre‑approved connectors, asking for confirmation before taking sensitive actions. Demonstrations showed agents preparing itineraries, assembling sales pipeline reports from mail and CRM sources, and drafting slide decks from collections of documents. Reviewers reported time savings on research, planning and first‑drafting repetitive artefacts, though others described frustrations, from slow progress on dynamic sites to difficulty with login walls and CAPTCHA challenges, occasional misread receipts or awkward format choices, and a tendency to stall or drop out of agent mode under load. The practical reading is direct. For workflows bounded by known data sources and repeatable steps, the approach is usable today provided the persistence of a human in the loop; for brittle, time‑sensitive or authentication‑heavy tasks, oversight remains essential.

As builders considered where to place effort, an architectural debate moved towards integration rather than displacement. Retrieval‑augmented generation remains a mainstay for grounding responses in authoritative content, reducing hallucinations and offering citations. The Model Context Protocol is emerging as a way to give models live, structured access to systems and data without pre‑indexing, with a growing catalogue of MCP servers behaving like interoperable plug‑ins. On top sits a layer of agent‑to‑agent protocols that allow specialised systems to collaborate across boundaries. Long contexts help with single‑shot ingestion of larger materials, retrieval suits source‑of‑truth answers and auditability, MCP handles current data and action primitives, and agents orchestrate steps and approvals. Some developers even describe MCP as an accidental universal adaptor because each connector built for one assistant becomes available to any MCP‑aware tool, a network effect that invites combinations across software.

Research results widened the lens. Meta’s fundamental AI research team took first place in the Algonauts 2025 brain modelling competition with TRIBE, a one‑billion‑parameter network that predicts human brain activity from films by analysing video, audio and dialogue together. Trained on subjects who watched eighty hours of television and cinema, the system correctly predicted more than half of measured activation patterns across a thousand brain regions and performed best where sight, sound and language converge, with accuracy in frontal regions linked with attention, decision‑making and emotional responses standing out. NASA and Google advanced a different type of applied science with the Crew Medical Officer Digital Assistant, an AI system intended to help astronauts diagnose and manage medical issues during deep‑space missions when real‑time contact with Earth may be impossible. Running on Vertex AI and using open‑source models such as Llama 3 and Mistral‑3 Small, early tests reported up to 88 per cent accuracy for certain injury diagnoses, with a roadmap that includes ultrasound imaging, biometrics and space‑specific conditions and implications for remote healthcare on Earth. In drug discovery, researchers at KAIST introduced BInD, a diffusion model that designs both molecules and their binding modes to diseased proteins in a single step, simultaneously optimising for selectivity, safety, stability and manufacturability and reusing successful strategies through a recycling technique that accelerates subsequent designs. In parallel, MIT scientists reported two AI‑designed antibiotics, NG1 and DN1, that showed promise against drug‑resistant gonorrhoea and MRSA in mice after screening tens of millions of theoretical compounds for efficacy and safety, prompting talk of a renewed period for antibiotic discovery. A further collaboration between NASA and IBM produced Surya, an open‑sourced foundation model trained on nine years of solar observations that improves forecasts of solar flares and space weather.

Security stories accompanied the acceleration. Researchers reported that GPT‑5 had been jailbroken shortly after release via task‑in‑prompt attacks that hide malicious intent within ciphered instructions, an approach that also worked against other leading systems, with defences reportedly catching fewer than one in five attempts. Roblox’s decision to open‑source a child‑safety moderation model reads as a complementary move to equip more platforms to filter harmful content, while Tenable announced capabilities to give enterprises visibility into how teams use AI and how internal systems are secured. Observability and reliability remained on the agenda, with predictions from Google and Datadog leaders about how organisations will scale their monitoring and build trust in AI outputs. Separate research from the UK’s AI Security Institute suggested that leading chatbots can shift people’s political views in under ten minutes of conversation, with effects that partially persist a month later, underscoring the importance of safeguards and transparency when systems become persuasive.

Industry manoeuvres were brisk. Former OpenAI researcher Leopold Aschenbrenner assembled more than $1.5 billion for a hedge fund themed around AI’s trajectory and reported a 47 per cent return in the first half of the year, focusing on semiconductor, infrastructure and power companies positioned to benefit from AI demand. A recruitment wave spread through AI labs targeting quantitative researchers from top trading firms, with generous pay offers and equity packages replacing traditional bonus structures. Advocates argue that quants’ expertise in latency, handling unstructured data and disciplined analysis maps well onto AI safety and performance problems; trading firms counter by questioning culture, structure and the depth of talent that startups can secure at speed. Microsoft went on the offensive for Meta’s AI talent, reportedly matching compensation with multi‑million offers using special recruiting teams and fast‑track approvals under the guidance of Mustafa Suleyman and former Meta engineer Jay Parikh. Funding rounds continued, with Cohere announcing $500 million at a $6.8 billion valuation and Cognition, the coding assistant startup, raising $500 million at a $9.8 billion valuation. In a related thread, internal notes at Meta pointed to the company formalising its superintelligence structure with Meta Superintelligence Labs, and subsequent reports suggested that Scale AI cofounder Alexandr Wang would take a leading role over Nat Friedman and Yann LeCun. Further updates added that Meta reorganised its AI division into research, training, products and infrastructure teams under Wang, dissolved its AGI Foundations group, introduced a ‘TBD Lab’ for frontier work, imposed a hiring freeze requiring Wang’s personal approval, and moved for Chief Scientist Yann LeCun to report to him.

The spotlight on superintelligence brightened in parallel. Analysts noted that technology giants are deploying an estimated $344 billion in 2025 alone towards this goal, with individual researcher compensation reported as high as $250 million in extreme cases and Meta assembling a highly paid team with packages in the eight figures. The strategic message to enterprises is clear: leaders have a narrow window to establish partnerships, infrastructure and workforce preparation before superintelligent capabilities reshape competitive dynamics. In that context, Meta announced Meta Superintelligence Labs and a 49 per cent stake in Scale AI for $14.3 billion, bringing founder Alexandr Wang onboard as chief AI officer and complementing widely reported senior hires, backed by infrastructure plans that include an AI supercluster called Prometheus slated for 2026. OpenAI began the year by stating it is confident it knows how to build AGI as traditionally understood, and has turned its attention to superintelligence. On one notable reasoning benchmark, ARC‑AGI‑2, GPT‑5 (High) was reported at 9.9 per cent at about seventy‑three cents per task, while Grok 4 (Thinking) scored closer to 16 per cent at a higher per‑task cost. Google, through DeepMind, adopted a measured but ambitious approach, coupling scientific breakthroughs with product updates such as Veo 3 for advanced video generation and a broader rethinking of search via an AI mode, while Safe Superintelligence reportedly drew a valuation of $32 billion. Timelines compressed in public discourse from decades to years, bringing into focus challenges in long‑context reasoning, safe self‑improvement, alignment and generalisation, and raising the question of whether co‑operation or competition is the safer route at this scale.

Geopolitics and policy remained in view. Reports surfaced that Nvidia and AMD had agreed to remit 15 per cent of their Chinese AI chip revenues to the United States government in exchange for export licences, a measure that could generate around $1 billion a quarter if sales return to prior levels, while Beijing was said to be discouraging use of Nvidia’s H20 processors in government and security‑sensitive contexts. The United States reportedly began secretly placing tracking devices in shipments of advanced AI chips to identify potential reroutings to China. In the United Kingdom, staff at the Alan Turing Institute lodged concerns about governance and strategic direction with the Charity Commission, while the government pressed for a refocusing on national priorities and defence‑linked work. In the private sector, SoftBank acquired Foxconn’s US electric‑vehicle plant as part of plans for a large‑scale data centre complex called Stargate. Tesla confirmed the closure of its Dojo supercomputer team to prioritise chip development, saying that all paths converged to AI6 and leaving a planned Dojo 2 as an evolutionary dead end. Focus shifted to two chips—AI5 manufactured by TSMC for the Full Self‑Driving system, and AI6 made by Samsung for autonomous driving and humanoid robots, with power for large‑scale AI training as well. Rather than splitting resources, Tesla plans to place multiple AI5 and AI6 chips on a single board to reduce cabling complexity and cost, a configuration Elon Musk joked could be considered “Dojo 3”. Dojo was first unveiled in 2019 as a key piece of autonomy ambitions, though attention moved in 2024 to a large training supercluster code-named Cortex, whose status remains unclear. These changes arrive amid falling EV sales, brand challenges, and a limited robotaxi launch in Austin that drew incident reports. Elsewhere, Bloomberg reported further departures from Apple’s foundation models group, with a researcher leaving for Meta.

The public face of AI turned combative as Altman and Musk traded accusations on X. Musk claimed legal action against Apple over alleged App Store favouritism towards OpenAI and suppression of rivals such as Grok. Altman disputed the premise and pointed to outcomes on X that he suggested reflected algorithmic choices; Musk replied with examples and suggested that bot activity was driving engagement patterns. Even automated accounts were drawn in, with Grok’s feed backing Altman’s point about algorithm changes, and a screenshot circulated that showed GPT‑5 ranking Musk as more trustworthy than Altman. In the background, reports emerged that OpenAI’s venture arm plans to lead funding in Merge Labs, a brain–computer interface startup co‑founded by Altman and positioned as a competitor to Musk’s Neuralink, whose goals include implanting twenty thousand people a year by 2031 and generating $1 billion in revenue. Distribution did not escape the theatrics either. Perplexity, which has been pushing an AI‑first browsing experience, reportedly made an unsolicited $34.5 billion bid for Google’s Chrome browser, proposing to keep Google as the default search while continuing support for Chromium. It landed as Google faces antitrust cases in the United States and as observers debated whether regulators might compel divestments. With Chrome’s user base in the billions and estimates of its value running far beyond the bid, the offer read to many as a headline‑seeking gambit rather than a plausible transaction, but it underlined a point repeated throughout the month: as building and copying software becomes easier, distribution is the battleground that matters most.

Product news and practical guidance continued despite the drama. Users can enable access to historical ChatGPT models via a simple setting, restoring earlier options such as GPT‑4o alongside GPT‑5. OpenAI’s new open‑source models under the GPT‑OSS banner can run locally using tools such as Ollama or LM Studio, offering privacy, offline access and zero‑cost inference for those willing to manage a download of around 13 gigabytes for the twenty‑billion‑parameter variant. Tutorials for agent builders described meeting‑prep assistants that scrape calendars, conduct short research runs before calls and draft emails, starting simply and layering integrations as confidence grows. Consumer audio moved with ElevenLabs adding text‑to‑track generation with editable sections and multiple variants, while Google introduced temporary chats and a Personal Context feature for Gemini so that it can reference past conversations and learn preferences, alongside higher rate limits for Deep Think. New releases kept arriving, from Liquid AI’s open‑weight vision–language models designed for speed on consumer devices and Tencent’s Hunyuan‑Vision‑Large appearing near the top of public multimodal leaderboards to Higgsfield AI’s Draw‑to‑Video for steering video output with sketches. Personnel changes continued as Igor Babuschkin left xAI to launch an investment firm and Anthropic acquired the co‑founders and several staff from Humanloop, an enterprise AI evaluation and safety platform.

Google’s own showcase underlined how phones and homes are becoming canvases for AI features. The Pixel 10 line placed Gemini across the range with visual overlays for the camera, a proactive cueing assistant, tools for call translation and message handling, and features such as Pixel Journal. Tensor G5, built by TSMC, brought a reported 60 per cent uplift for on‑device AI processing. Gemini for Home promised more capable domestic assistance, while Fitbit and Pixel Watch 4 introduced conversational health coaching and Pixel Buds added head‑gesture controls. Against that backdrop, Google published details on Gemini’s environmental footprint, claiming the model consumes energy equivalent to watching nine seconds of television per text request and “five drops of water” per query, while saying efficiency improved markedly over the past year. Researchers challenged the framing, arguing that indirect water used by power generation is under‑counted and calling for comparable, third‑party standards. Elsewhere in search and productivity, Google expanded access to an AI mode for conversational search, and agreements emerged to push adoption in public agencies at low unit pricing.

Attention also turned to compact models and devices. Google released Gemma 3 270M, an ultra‑compact open model that can run on smartphones and browsers while eking out notable efficiency, with internal tests reporting that 25 conversations on a Pixel 9 Pro consumed less than one per cent of the battery and quick fine‑tuning enabling offline tasks such as a bedtime story generator. Anthropic broadened access to its Learning Mode, which guides people towards answers rather than simply supplying them, and now includes an explanatory coding mode. On the hardware side, HTC introduced Vive Eagle, AI glasses that allow switching between assistants from OpenAI and Google via a “Hey Vive” command, with on‑device processing for features such as real‑time photo‑based translation across thirteen languages, an ultra‑wide camera, extended battery life and media capture, currently limited to Taiwan.

Behind many deployments sits a familiar requirement: secure, compliant handling of data and a disciplined approach to roll‑out. Case studies from large industrial players point to the bedrock steps that enable scale. Lockheed Martin’s work with IBM on watsonx began with reducing tool sprawl and building a unified data environment capable of serving ten thousand engineers; the result has been faster product teams and a measurable boost in internal answer accuracy. Governance frameworks for AI, including those provided by vendors in security and compliance, are moving from optional extras to prerequisites for enterprise adoption. Organisations exploring agentic systems in particular will need clear approval gates, auditing and defaults that err on the side of caution when sensitive actions are in play.

Broader infrastructure questions loomed over these developments. Analysts projected that AI hyperscalers may spend around $2.9 trillion on data centres through to 2029, with a funding gap of about $1.5 trillion after likely commitments from established technology firms, prompting a rise in debt financing for large projects. Private capital has been active in supplying loans, and Meta recently arranged a large facility reported at $29 billion, most of it debt, to advance data centre expansion. The scale has prompted concerns about overcapacity, energy demand and the risk of rapid obsolescence, reducing returns for owners. In parallel, Google partnered with the Tennessee Valley Authority to buy electricity from Kairos Power’s Hermes 2 molten‑salt reactor in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, targeting operation around 2030. The 50 MW unit is positioned as a step towards 500 MW of new nuclear capacity by 2035 to serve data centres in the region, with clean energy certificates expected through TVA.

Consumer and enterprise services pressed on around the edges. Microsoft prepared lightweight companion apps for Microsoft 365 in the Windows 11 taskbar. Skyrora became the first UK company licensed for rocket launches from SaxaVord Spaceport. VIP Play announced personalised sports audio. Google expanded availability of its Imagen 4 model with higher resolution options. Former Twitter chief executive Parag Agrawal introduced Parallel, a startup offering a web API designed for AI agents. Deutsche Telekom launched an AI phone and tablet integrated with Perplexity’s assistant. Meta faced scrutiny after reports about an internal policy document describing permitted outputs that included romantic conversations with minors, which the company disputed and moved to correct.

Healthcare illustrated both promise and caution. Alongside the space‑medicine assistant, the antibiotics work and NASA’s solar model, a study reported that routine use of AI during colonoscopies may reduce the skill levels of healthcare professionals, a finding that could have wider implications in domains where human judgement is critical and joining a broader conversation about preserving expertise as assistance becomes ubiquitous. Practical guides continued to surface, from instructions for creating realistic AI voices using native speech generation to automating web monitoring with agents that watch for updates and deliver alerts by email. Bill Gates added a funding incentive to the medical side with a $1 million Alzheimer’s Insights AI Prize seeking agents that autonomously analyse decades of research data, with the winner to be made freely available to scientists.

Apple’s plans added a longer‑term note by looking beyond phones and laptops. Reports suggested that the company is pushing for a smart‑home expansion with four AI‑powered devices, including a desktop robot with a motorised arm that can track users and lock onto speakers, a smart display and new security cameras, with launches aimed between 2026 and 2027. A personality‑driven character for a new Siri called Bubbles was described, while engineers are reportedly rebuilding Siri from scratch with AI models under the codename Linwood and testing Anthropic’s Claude as a backup code-named Glenwood. Alongside those ambitions sit nearer‑term updates. Apple has been preparing a significant Siri upgrade based on a new App Intents system that aims to let people run apps entirely by voice, from photo edits to adding items to a basket, with a testing programme under way before a broader release and accuracy concerns prompting a limited initial rollout across selected apps. In the background, Tim Cook pledged to make all iPhone and Apple Watch cover glass in the United States, though much of the production process will remain overseas, and work on iOS 26 and Liquid Glass 1.0 was said to be nearing completion with smoother performance and small design tweaks. Hiring currents persist as Meta continues to recruit from Apple’s models team.

Other platforms and services added their own strands. Google introduced Personal Context for Gemini to remember chat history and preferences and added temporary chats that expire after seventy‑two hours, while confirming a duplicate event feature for Calendar after a public request. Meta’s Threads crossed 400 million monthly active users, building a real‑time text dataset that may prove useful for future training. Funding news continued as Profound raised $35 million to build an AI search platform and Squint raised $40 million to modernise manufacturing with AI. Lighter snippets appeared too, from a claim that beards can provide up to SPF 21 of sun protection to a report on X that an AI coding agent had deleted a production database, a reminder of the need for careful sandboxing of tools. Gaming‑style benchmarks surfaced, with GPT‑5 reportedly earning eight badges in Pokémon Red in 6,000 steps, while DeepSeek’s R2 model was said to be delayed due to training issues with Huawei’s Ascend chips. Senators in the United States called for a probe into Meta’s AI policies following controversy about chatbot outputs, reports suggested that the US government was exploring a stake in Intel, and T‑Mobile’s parent launched devices in Europe featuring Perplexity’s assistant.

Perhaps the most consequential lesson from the period is simple. Progress in capability is rapid, as competition results, research papers and new features attest. Yet adoption is being steered by human factors: the preference for a known voice, the desire for choice and control, and understandable scepticism when new modes do not perform as promised on day one. GPT‑5’s early missteps forced a course correction that restored a familiar option and increased transparency around limits and modes. The agentic turn is showing real value in constrained workflows, but still benefits from patience and supervision. Architecture debates are converging on combinations rather than replacements. And amid bold bids, public quarrels, hefty capital outlays and cautionary studies on enterprise returns, the work of making AI useful, safe and dependable continues, one model update and one workflow at a time.

How to adjust Adobe Lightroom Classic font sizes beyond the default options

25th November 2022Earlier in the year, I upgraded my monitor to a 34-inch widescreen Iiyama XUB3493WQSU. At the time, I was in wonderment at what I was doing, even if I have grown used to it now. For one thing, it made the onscreen text too small, so I ended up having to scale things up in both Linux and Windows. The former turned out to be more malleable than the latter, and that impression also applies to the main subject of this piece.

What I also found is that I needed to scale the user interface font sizes within Adobe Lightroom Classic running within a Windows virtual machine on VirtualBox. That can be done by going to Edit > Preferences through the menus and then going to the Interface tab in the dialogue box that appears where you can change the Font Size setting using the dropdown menu and confirm changes using the OK button.

However, the range of options is limited. Medium appears to be the default setting, while the others include Small, Large, Larger and Largest. Large scales by 150%, Larger by 200% and Largest by 250%. Of these, Large was the setting that I chose, though it always felt too big to me.

Out of curiosity, I decided to probe further, only to find extra possibilities that could be selected by direct editing of a configuration file. This file is called Lightroom Classic CC 7 Preferences.agprefs and can be found in C:\Users\[user account]\AppData\Roaming\Adobe\Lightroom\Preferences. In there, you need to find the line containing AgPanel_baseFontSize and change the value enclosed within quotes and save the file. Taking a backup beforehand is wise, even if the modification is not a major one.

The available choices are scale125, scale140, scale150, scale175, scale180, scale200 and scale250. Some of these may be recognisable as those available through the Lightroom Classic user interface. In my case, I chose the first on the list, so the line in the configuration file became:

AgPanel_baseFontSize="scale125"

While there may be good reasons for the additional options not being available through the user interface, things are working out OK for me for now. It is another tweak that helps me to get used to the larger screen size and its higher resolution.

Evolving a photo editing workflow to make more use of Adobe Lightroom than before

17th April 2018Photo editing has been something that I have been doing since my first-ever photo scan in 1998 (I believe it was in June of that year but cannot be completely sure nearly twenty years later). Since then, I have been using various tools for the job and wondered how other photos can look better than my own. What cannot be excluded is my preference for being active in the middle of the day when light is at its bluest, as well as a penchant for using a higher ISO of 400. In other words, what I do when making photos affects how they look afterwards as much as the weather that I had encountered.

My reason for mentioning the above aspects of photographic craft is that they affect what you can do in photo editing afterwards, even with the benefits of technological advancement. My tastes have changed over time, so the appeal of re-editing old photos fades when you realise that you only are going around in circles and there always are new ones to share, so that may be a better way to improve.

When I started, I was a user of Paint Shop Pro but have gone over to Adobe since then. First, it was Photoshop Elements, but an offer in 2011 lured me into having Lightroom and the full version of Photoshop. Nowadays, I am a Creative Cloud photography plan subscriber, so I get to see new developments much sooner than once was the case.

Even though I have had Lightroom for all that time, I never really made full use of it and preferred a Photoshop-based workflow. Lightroom was used to select photos for Photoshop editing, mainly using adjustments for such things as tones, exposure, levels, hue and saturation. Removal of dust spots, resizing and sharpening were other parts of a still minimalist approach.

What changed all this was a day spent pottering about the 2018 Photography Show at the Birmingham NEC during a cold snap in March. That was followed by my checking out the Adobe YouTube Channel afterwards, where there were videos of the talks featured every day of the four-day event. Here are some shortcuts if you want to do some catching up yourself: Day 1, Day 2, Day 3, and Day 4. Be warned though that these videos are long in that they feature the whole day and there are enough gaps that you may wish to fast-forward through them. Even so, there is quite a bit of variety of things to see.

Of particular interest were the talks given by the landscape photographer David Noton who sensibly has a philosophy of doing as little to his images as possible. It helps that his starting points are so good that adjusting black and white points with a little tonal adjustment does most of what he needs. Vibrancy, clarity and sharpening adjustments are kept to a minimum, while some work with graduated filters evens out exposure differences between skies and landscapes. It helps that all this can be done in Lightroom, so that set me thinking about trying it out for size, and the trick of using the backslash () key to switch between raw and processed views is a bonus granted by non-destructive editing. Others may have demonstrated the creation of composite imagery, but simplicity is more like my way of working.

It is confusing that we now have cloud-based Lightroom CC, while the previous desktop version is called Lightroom Classic CC. Although the former offers easy dust spot removal and other features, I prefer the latter because I do not want to upload my entire image library, and I already use Google Drive and Dropbox for off-site backup. The mobile app is interesting since it allows capturing images on mobile devices in Adobe's raw DNG format. My workflow is now more Lightroom-based than before, and I appreciate the new technology, especially as Adobe develops its Sensai artificial intelligence engine. Because Adobe has access to numerous images through Lightroom CC and Adobe Stock (formerly Fotolia), it has abundant data to train this AI system.

Batch conversion of DNG files to other file types with the Linux command line

8th June 2016At the time of writing, Google Drive is unable to accept DNG files, the Adobe file type for RAW images from digital cameras. While the uploads themselves work fine, the additional processing at the end that, I believe, is needed for Google Photos appears to be failing. Because of this, I thought of other possibilities like uploading them to Dropbox or enclosing them in ZIP archives instead; of these, it is the first that I have been doing and with nothing but success so far. Another idea is to convert the files into an image format that Google Drive can handle, and TIFF came to mind because it keeps all the detail from the original image. In contrast, JPEG files lose some information because of the nature of the compression.

Handily, a one line command does the conversion for all files in a directory once you have all the required software installed:

find -type f | grep -i "DNG" | parallel mogrify -format tiff {}

The find and grep commands are standard, with the first getting you a list of all the files in the current directory and sending (piping) these to the grep command, so the list only retains the names of all DNG files. The last part uses two commands for which I found installation was needed on my Linux Mint machine. The parallel package is the first of these and distributes the heavy workload across all the cores in your processor, and this command will add it to your system:

sudo apt-get install parallel

The mogrify command is part of the ImageMagick suite along with others like convert and this is how you add that to your system:

sudo apt-get install imagemagick

In the command at the top, the parallel command works through all the files in the list provided to it and feeds them to mogrify for conversion. Without the use of parallel, the basic command is like this:

mogrify -format tiff *.DNG

In both cases, the -format switch specifies the output file type, with the tiff portion triggering the creation of TIFF files. The *.DNG portion itself captures all DNG files in a directory, but {} does this in the main command at the top of this post. If you wanted JPEG ones, you would replace tiff with jpg. Should you ever need them, a full list of what file types are supported is produced using the identify command (also part of ImageMagick) as follows:

identify -list format

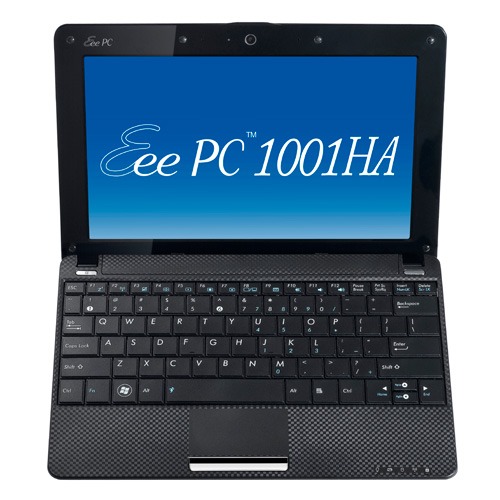

Portable computing with the Asus Eee PC 1001 HA

7th October 2010Having had an Asus Eee PC 1001 HA for a few weeks now, I thought that it might be opportune to share a few words about the thing on here. The first thing that struck me when I got it was the size of the box in which it came. Being accustomed to things coming in large boxes meant the relatively diminutive size of the package was hard not to notice. Within that small box was the netbook itself, along with the requisite power cable and not much else apart from warranty and quick-start guides; so that's how they kept things small.

Though I was well aware of the size of a netbook from previous bouts of window shopping, the small size of something with a 10" screen hadn't embedded itself into my consciousness. Despite that, it came with more items that reflect desktop computing than might be expected. First, there's a 160 GB hard disk and 1 GB of memory, neither of which is disgraceful and the memory module sits behind a panel opened by loosening a screw, which leaves me wondering about adding more. Sockets for network and VGA cables are included, along with three USB ports and sockets for a set of headphones and for a microphone. Portability starts to come to the fore with the inclusion of an Intel Atom CPU and a socket for an SD card. Unusual inclusions come in the form of an onboard webcam and microphone, both of which I intend to leave in the off position for the sake of privacy. Wi-Fi is another networking option, so you're not short of features. The keyboard is not too compromised either, and the mouse trackpad is the sort of thing that you'd find on full-size laptops. With the latter, you can use gestures too, so I need to learn what ones are available.

The operating system that comes with the machine is Windows XP, and there are some extras bundled with it. These include a trial of Trend Micro as an initial security software option, as well as Microsoft Works and a trial of Microsoft Office 2007. Then, there are some Asus utilities too, though they are not so useful to me. All in all, none of these burden the processing power too much and IE8 comes installed too. Being a tinkerer, I have put some of the sorts of things that I'd have on a full-size PC on there. Examples include Mozilla Firefox, Google Chrome, Adobe Reader and Adobe Digital Editions. Pushing the boat out further, I used Wubi to get Ubuntu 10.04 on there in the same way as I have done with my 15" Toshiba laptop. So far, nothing seems to overwhelm the available processing power, though I am left wondering about battery life.

The mention of battery life brings me to mulling over how well the machine operates. So far, I am finding that the battery lasts around three hours, much longer than on my Toshiba but nothing startling either. Nevertheless, it does preserve things by going into sleep mode when you leave it unattended for long enough. Still, I'd be inclined to find a socket if I was undertaking a long train journey.

According to the specifications, it is supposed to weigh around 1.4 kg and that seems not to be a weight that has been a burden to carry so far and the smaller size makes it easy to pop into any bag. It also seems sufficiently robust to allow its carrying by bicycle, though I wouldn't be inclined to carry it over too many rough roads. In fact, the manufacturer advises against carrying it anywhere (by bike or otherwise) without switching it off first, but that's a common-sense precaution.

Start-up times are respectable, though you feel the time going by when you're on a bus for a forty-minute journey, and shutdown needs some time set aside near the end. The screen resolution can be increased to 1024x600 and the shallowness can be noticed, reminding you that you are using a portable machine. For that reason, there have been times when I hit the F11 key to get a full-screen web browser session. Coupled with the Vodafone mobile broadband dongle that I have, it has done some useful things for me while on the move so long as there is sufficient signal strength (seeing the type of connection change between 3G, EDGE and GPRS is instructive). All in all, it's not a chore to use, as long as Internet connections aren't temperamental.

Why the manual step? Upgrading Camera Raw in Photoshop Elements 7

18th January 2010One of the consequences of buying a new camera is that your current photo processing software may not be fully equipped for the job of handling the images that it creates. This especially manifests itself with raw image files; Adobe Photoshop Elements 5 was unable to completely handle DNG files made with my Pentax K10D until I upgraded to version 7.

As things stood, Elements 7 was unable to import CR2 files from my Canon PowerShot G11 into the Organiser, so it was off to the appropriate page on the Adobe website for a Camera Raw updater. Thus, I picked up the latest release of Camera Raw (5.6 at the time of writing) even though it was found in the Elements 8 category (don't be put by this because release notes address the version compatibility question more extensively).

Strangely, the updater doesn't complete everything because you still need to copy Camera Raw.8bi from the zip archive and backup the original. Quite why this couldn't have been more automated, even with user prompts for file names and locations, is beyond me, yet that is how it is. However, once all was in place, CR2 files were handled by Elements without missing a beat.

So you just need a web browser?

21st November 2009When Google announced that it was working on an operating system, it was bound to result in a frisson of excitement. However, a peek at the preview edition that has been doing the rounds confirms that Chrome OS is a very different beast from those operating systems to which we are accustomed. The first thing that you notice is that it only starts up the Chrome web browser. In this, it is like a Windows terminal server session that opens just one application. Of course, in Google's case, that one piece of software is the gateway to its usual collection of productivity software like Gmail, Calendar, Docs & Spreadsheets and more. Then, there are offerings from others too, with Microsoft just beginning to come into the fray to join Adobe and many more. As far as I can tell, all files are stored remotely, so I reckon that adding the possibility of local storage and management of those local files would be a useful enhancement.

With Chrome OS, Google's general strategy starts to make sense. First create a raft of web applications, follow them up with a browser and then knock up an operating system. It just goes to show that Google Labs doesn't simply churn out stuff for fun, but that there is a serious point to their endeavours. In fact, you could say that they sucked us in to a point along the way. Speaking for myself, I may not entrust all of my files to storage in the cloud, yet I am perfectly happy to entrust all of my personal email activity to Gmail. It's the widespread availability and platform independence that has done it for me. For others spread between one place and another, the attractions of Google's other web apps cannot be understated. Maybe, that's why they are not the only players in the field either.

With the rise of mobile computing, that kine of portability is the opportunity that Google is trying to use to its advantage. For example, mobile phones are being used for things now that would have been unthinkable a few years back. Then, there's the netbook revolution started by Asus with its Eee PC. All of this is creating an ever internet connected bunch of people, so having devices that connect straight to the web like they would with Chrome OS has to be a smart move. Some may decry the idea that Chrome OS will be available on a device only basis, but I suppose they have to make money from this too; search can only pay for so much, and they have experience with Android too.